Raven, the trickster of the Northwest coast, visited us this morning. He took the sun from wherever he had been hiding it, tossed it into the sky, and it shone brightly on us as we began our visit to Haida Gwaii.

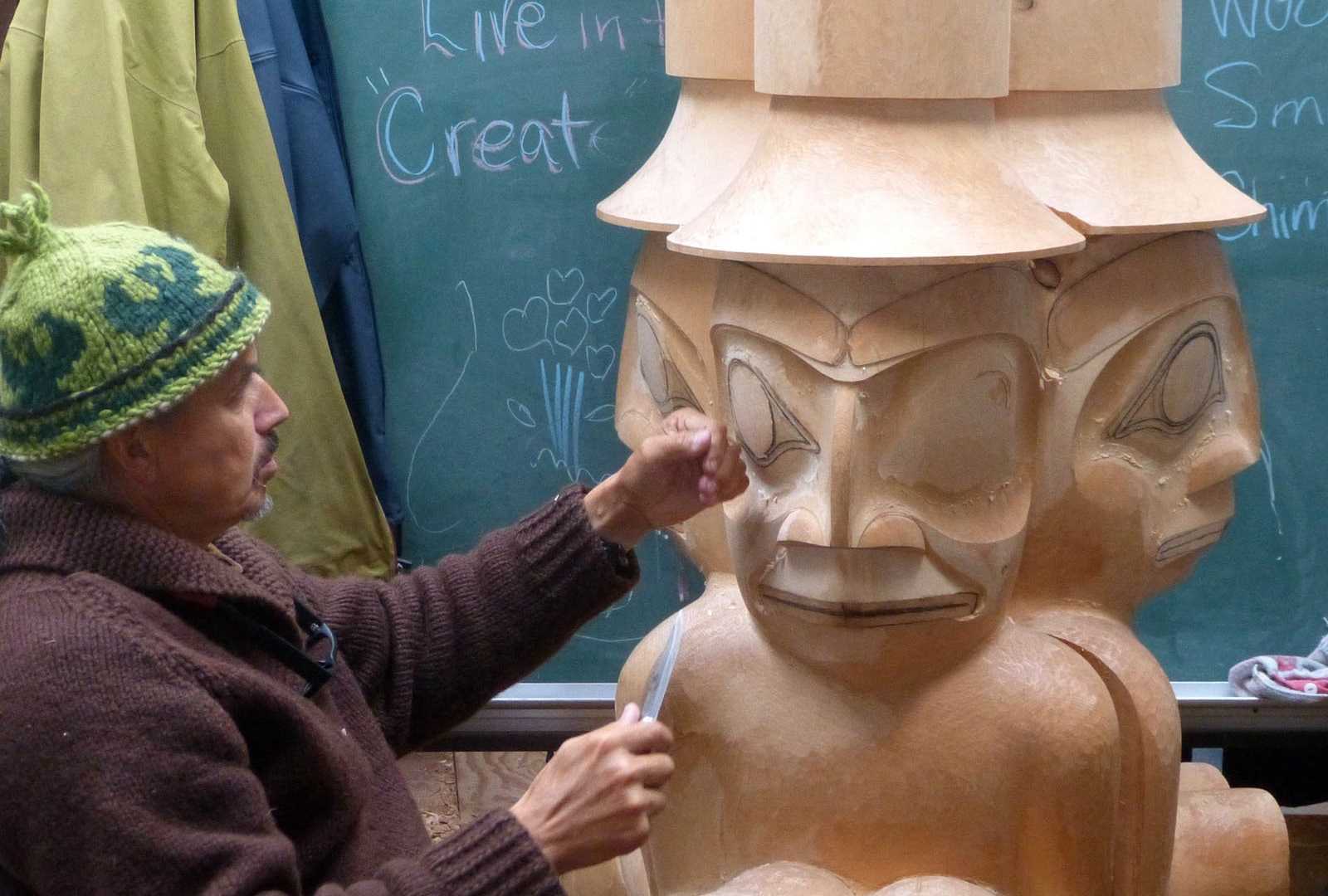

We boarded the Haida Gwaii version of luxury transportation and headed north over the only paved road to reach the community of Old Massett. It is the center of a resurgence of Haida culture that began in 1969 when the first totem pole to be erected in over 100 years was raised here. Now, a number of widely recognized carvers, artists, and canoe-builders live and work here in Old Massett, passing on their traditions to the next generation. One of the carvers is Jim Hart, known by his Haida chief name of Uidansuu. He holds a hereditary chiefdom, which, by Haida tradition in this matrilineal society, was inherited from his maternal uncle. We found him, with his son, working on a large pole, carved in the round from a Western redcedar log. Haida art is evolving, and this pole is an example. It is carved in traditional form line design, but the theme is one of reconciliation, as the Haida struggle to recover from the dark days when their children were taken from their home communities by the government and sent away to boarding schools in an attempt to exterminate their language and culture. (The Canadian government has formally apologized to their First Nations people for the abuses of this era.) The pole includes an image of the government school, not exactly a traditional design feature. All the while, as he described the pole and the carving process, Uidansuu and his son continued their work. When it is completed next month, this massive pole will be erected in Vancouver, a process that will take some 800 people pulling on ropes, and culminate in a grand celebration of Haida culture, all under the supervision of the chief.

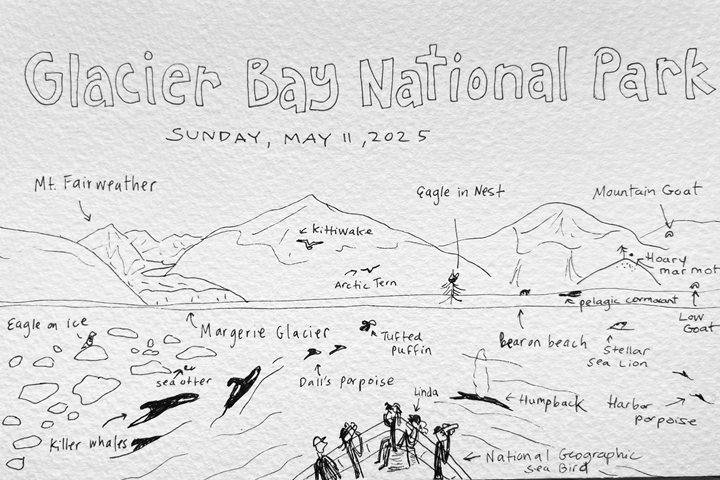

Christian White is another Haida carver, community leader, and keeper of the culture. He greeted us next to a totem pole of his own carving, made to stand in front of the longhouse of traditional design that he has constructed. In his carving shed, he told us of the canoes that he has carved and the long sea voyages that he has undertaken in them, attesting to the remarkable seaworthiness of their design. He spoke of Haida stories. In the absence of a written language, their history is passed down from one generation to the next in the form of their stories. What we once called myth we now recognize as oral history, and it is remarkably rich. A lunch of Haida foods from the land and sea of Haida Gwaii - salmon, kelp, and soapberries - was served in the longhouse. When the tables were cleared, our hosts appeared in their dance regalia. The dancers wore elaborate masks depicting raven, eagle, and mythological creatures from their stories. As the finale, National Geographic Sea Bird guests were invited to join in the final dances, which we did with gusto. We were pretty good.