As National Geographic Endurance sidled up to the fragile, early summer sea ice, nine statuesque birds – each a meter tall, cloaked in black and white with fiery orange accent patches behind their ears and beneath their chins that faded to creamy yellow before giving way to white bellies – looked over their shoulders as they plodded deeper into the ice. It’s no wonder, with their sleek, black trench coats open in the front and the downward gaze they cast on their smaller, pudgier cousins, that these are called emperor penguins.

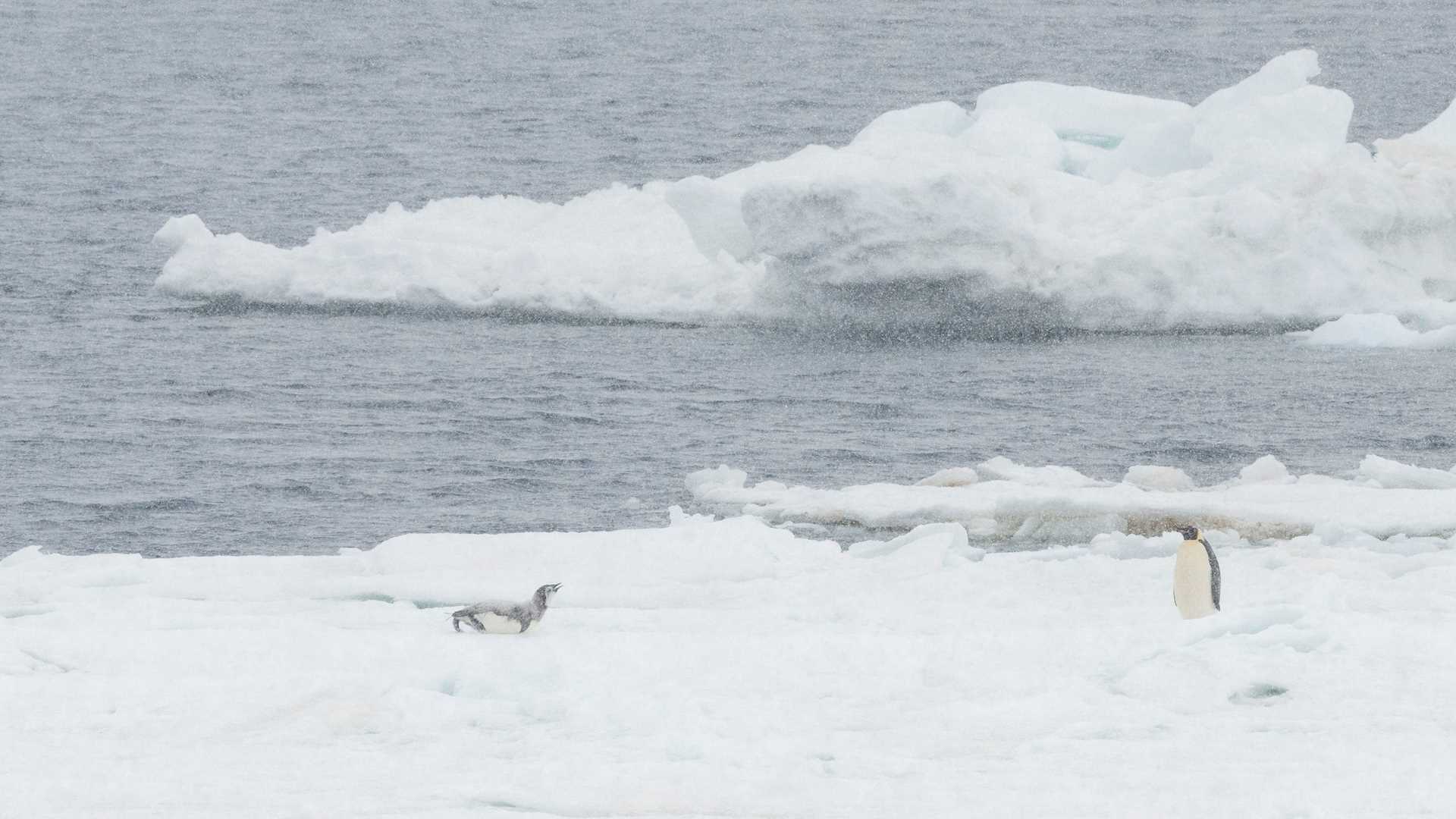

Snow Hill Island, home to the world’s northernmost emperor penguin colony, is, in early summer, only dotted here and there with small groups of the remaining members of this species that lays eggs and incubates through the austral winter. Nine in this group, four in the next, a gathering of thirty a few hundred yards away, and a single parent and chick, visible with binoculars through blowing snow.

For this writer, the distant penguin assemblages, scattered about the frozen landscape, increased lifetime sightings exponentially. For most guests and some staff, the few hundred birds the morning provided represented the sum, and possibly the only, emperor penguins they will ever see.

As a warming climate robs Antarctica of annual pack ice, we wonder how long opportunities like this will occur, and if some of us on board will see the day when emperors no longer raise their young in the Weddell Sea. These questions dominate conversations around the lounge this evening as we look back on the day, pinching ourselves, and appreciating how fortunate we are to be here now.